By Vance Barse, CPWA®, AIF®, Wealth Strategist & Founder of Your Dedicated Fiduciary ®

Vance Barse is the founder of Your Dedicated Fiduciary®, which serves as financial consultant and trusted advisor to roughly 50 families coast-to-coast and specializes in advanced planning for equestrians. After a decade as an investment consultant, Vance noticed planning gaps that left the clients of many private wealth financial advisors underserved. This observation, along with the conflicts of interest endemic to the industry, inspired Vance to leave his career and found his advisory firm “to be authentic, transparent, and have a positive impact on the lives of clients through an innovative planning paradigm.” He began to explore the equestrian industry upon a personal invitation from one of the families he serves, and upon the discovery that equestrian estates often require advanced planning solutions, he began to develop planning strategies with this unique community in mind.

Vance Barse is the founder of Your Dedicated Fiduciary®, which serves as financial consultant and trusted advisor to roughly 50 families coast-to-coast and specializes in advanced planning for equestrians. After a decade as an investment consultant, Vance noticed planning gaps that left the clients of many private wealth financial advisors underserved. This observation, along with the conflicts of interest endemic to the industry, inspired Vance to leave his career and found his advisory firm “to be authentic, transparent, and have a positive impact on the lives of clients through an innovative planning paradigm.” He began to explore the equestrian industry upon a personal invitation from one of the families he serves, and upon the discovery that equestrian estates often require advanced planning solutions, he began to develop planning strategies with this unique community in mind.

Vance is a Certified Private Wealth Advisor® (“CPWA®”) professional and also holds the Accredited Investment Fiduciary® (“AIF®”) designation. His firm also has a Certified Financial Planner (“CFP®”) on staff. He has been featured on CNBC, Bloomberg Radio, Investment News, MarketWatch and many more. He has also published “Fiduciary Wealth Management: The Millionaire’s Guide to Hiring the Right Financial Advisor,” which readers can request by clicking Contact.

Equestrians are known for being remarkably passionate people. One of the benefits of serving the riding community is the opportunity to implement purpose-driven philanthropy and observe the fulfillment it brings families with charitable intent—regardless of size. Many donors, though, default to bestowing cash directly to charity or choose to leave a philanthropic gift upon their transition to the spiritual side. This article introduces other tax-smart charitable planning strategies that may be more impactful by marrying passion and purpose for equine connoisseurs.

A PRÉCIS ON CHARITABLE GIVING

The cornerstone of understanding charitable giving is understanding the charitable contribution deduction and how it applies to various types of gifts. A taxpayer’s charitable deduction is subject to an overall limitation based on the taxpayer’s adjusted gross income (“AGI”). This limitation depends on whether the recipient organization is a public charity or a private foundation, and the type of property contributed. The AGI limitation rules can get rather technical, but it’s not rocket science.

Charitable deductions are generally equal to the fair-market value of the asset on the day that the charity takes ownership of the asset unless the asset has short-term appreciation. For a short-term appreciated asset, the deduction is equal to the basis. Charitable deductions to public charities are limited in each tax year to 60% of AGI for gifts of cash, and 30% of AGI for long-term appreciated assets. For contributions to a private foundation, deductions are generally limited to 30% of AGI for cash gifts, and 20% of AGI for long-term appreciated assets.

Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, it is important to remember that for you to itemize your charitable contribution deductions, your total itemized deductions must be more than the standard deduction, which, in 2021, is $12,550 for individuals and couples who are married filing separately, $25,100 for married couples filing jointly, and $18,800 for head of household. If you cannot fully use your charitable deduction in a tax year because of the AGI caps, you can carry forward any excess for up to five years.

COMMON CHARITABLE PLANNING VEHICLES

There are two main categories of charitable planning vehicles: irrevocable and split interest. There are three main types of irrevocable gifts: foundation, donor-advised fund (“DAF”) and qualified charitable distributions (“QCD”). Similarly, there are three main types of split-interest gifts: charitable remainder trust (“CRT”), charitable lead trust (“CLT”) and charitable gift annuity (“CGA”).

FOUNDATION

Families often vocalize an interest in establishing a foundation because of its appeal. However, upon further review, it is often costly and time-consuming to establish and maintain a foundation given the complex rules and restrictions, potential for high excise taxes, and lower AGI caps. Family foundations are often best for donations of $1mm+ or when the family is serving as primary research and/or charitable board, meaning substantial philanthropic activities, such as having boots on the ground conducting researching and donating directly to specific charitable recipients. Generally, a donor-advised fund is easier to manage and lower in cost, has higher AGI caps, and fosters familial unity.

DONOR – ADVISED FUND (“DAF”)

A DAF is a popular vehicle with several points of intrigue. The DAF allows donors to “bunch” future years’ charitable intent by contributing cash or highly appreciated, non-qualified assets such as stock or expensive and tax-inefficient mutual funds. There is an immediate deduction for the value of the donated asset, and there is no capital gains tax due on highly appreciated holdings that are sold within the DAF. The resulting cash can be invested in a portfolio, there is no grant requirement for a minimum distribution, and the DAF can be honorably named to recognize the family (e.g., “The Smith Family Charitable Giving Fund”). This vehicle can also be used to foster familial unity by teaching your core money and philanthropic values to the next generation, who can serve as successor trustee for continued disbursements to charities of their choice. Donors receive a deduction of up to 30% of AGI by donating highly appreciated, non-qualified assets and a deduction of up to 60% of AGI for donating cash.

QUALIFIED CHARITABLE DISTRIBUTION (“QCD”)

Per the IRS website, “Generally, a QCD is an otherwise taxable distribution from an IRA (other than an ongoing SEP or SIMPLE IRA) owned by an individual who is age 70½ or over that is paid directly from the IRA to a qualified charity.” Typically, QCDs are considered by taxpayers who must take their required minimum distributions (“RMDs”) and who also have charitable intent. The SECURE Act modified the RMD rules such that taxpayers who turned 70½ years of age in 2020 or later must take their RMDs by April 1 of the year in which they turn 72. The QCD does not hit your AGI, which means that the amount you withdraw from your IRA and donate as the QCD is not counted toward your AGI even though it is part of your retirement distribution. This can be beneficial for Medicare premiums or taxable social security. The maximum allowable QCD amount is $100,000 per year.

CHARITABLE REMAINDER TRUST (“CRT”)

With a CRT, you get an upfront deduction equal to the present value of the remainder interest and income stream; however, you will not avoid capital gains. In its basic form, a CRT pays an income interest to an individual (or individuals) for a term of years or lifetime, with the remainder assets passing to a charity. The annual income payment can either be a fixed dollar amount (in a charitable remainder annuity trust, or “CRAT”) or a percentage of the trust’s value calculated each year (in a charitable remainder unitrust, or “CRUT”). The trust itself is a tax-exempt entity, so if appreciated assets are sold within the trust, the trust will not owe any taxes. However, a donor can’t avoid capital gains by selling assets in a CRT because the trust builds up four tiers of taxable income that are passed out to the income beneficiary in the annuity or unitrust payment: 1) ordinary income (further broken down to ordinary income, then qualified dividends); 2) capital gains (further broken down into short-term capital gains, then a capital gain on the sale of collectibles, then a capital gain on sale of real property that is attributable to depreciation recapture, and then a capital gain on securities sales); 3) tax-free income; and 4) return of principal.

CHARITABLE LEAD TRUST (“CLT”)

A CLT offers an estate tax freeze and comes in two flavors: reversionary (“grantor lead”) and non-reversionary trusts. With grantor lead trusts, the grantor gets an upfront income tax deduction equal to the present value of the lead interest, but it is capped at 30%/20% of AGI because it is a gift for the use of the charity rather than to the charity. The grantor is taxed personally on all income, so these are generally funded with municipal bond investments and the assets typically revert back to the grantor at the end of the charitable lead term. In non-reversionary trusts, the grantor does not get an income tax deduction, the assets revert back to someone other than the grantor at the end of the charitable lead term, and the value of the assets in the trust grow outside of the grantor’s estate. The grantor can offset the amount of the gift to their heirs with the value of the charitable lead interest. As such, non-reversionary CLTs have often been used as an estate tax freeze technique: a substantial lifetime gift can be made to heirs with a reduced value, and assets can continue to appreciate.

CHARITABLE GIFT ANNUITY (“CGA”)

A CGA is established with a charity, such as the Red Cross, whereby the donor makes a charitable donation in exchange for an annuity for life. The donor gets a deduction equal to the difference between the present value of the annuity stream and the value of their contribution.

LISA AND KEN: ULTRA-HIGH NET WORTH ESTATE

Ken and Lisa run a wildly successful equine empire in Kentucky and have amassed a net worth of about $50mm, which is comprised of their business interests, several pieces of real property (one of which is worth $3mm that they are considering selling at a substantial gain soon), a fine art collection and several luxury cars. They have two children, to whom they wish to provide a substantial inheritance, and have a deep love for animals: together, they have 20 horses, 4 miniature ponies, 3 dogs and 2 swans. As a result of their love for Saddlebreds, Ken and Lisa are extremely philanthropic, with a focus on equine charities, and even founded their own public charity, the Saving Saddlebreds Mission.

Ken and Lisa would like to incorporate their philanthropic endeavors with their financial and estate planning needs, particularly as it relates to providing for their children and minimizing their substantial estate tax liability. There are several moving parts here, so please see Diagram 1 for guidance.

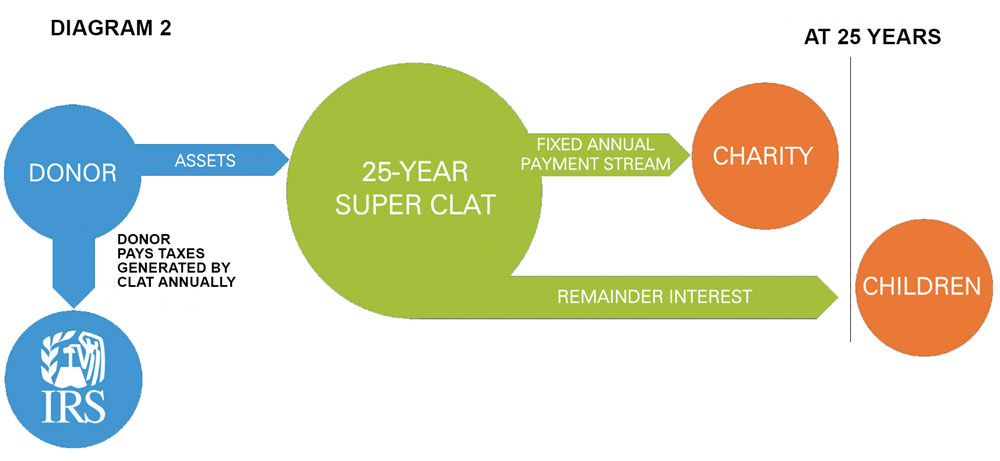

Their planning solution involves an iteration of a standard CRUT where the income stream that goes to the grantor is used to fund premiums on an insurance policy held by an Irrevocable Life Insurance Trust (“ILIT”). The income recipient (donor) contributes that income to an ILIT that ultimately passes the insurance death benefit to the income beneficiaries’ heirs at death to alleviate the estate tax burden.

Ken and Lisa want to preserve as much of their wealth for their children as possible while still meeting their philanthropic goals. Typically, a CRT would reduce a donor’s net worth but provide them with an income stream, as we saw with Kylie and Mauricio. For Ken and Lisa, however, income isn’t of concern, but preserving wealth is: this may call for the use of a CRT with a wealth replacement trust. In this case, they would take their appreciated vacation home valued at $3mm, put it into the CRUT, and income goes into the ILIT with a $3mm second-to-die policy with their kids as beneficiaries.

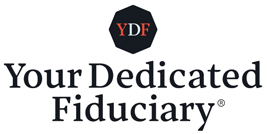

Another charitable giving vehicle that may have significant planning benefits for Ken and Lisa is a CLT (see “CLT” above for a refresher). In recent years, a hybrid technique has emerged called the “Super CLT” or “Intentionally Defective Grantor Charitable Lead Trust.” As shown in Diagram 2, a Super CLT is considered a grantor trust for income tax purposes, but a non-reversionary trust for gift and estate tax purposes. By transferring assets to a Super CLT, Ken and Lisa could receive an immediate income tax deduction, make a completed gift with a discounted value to their heirs, and remove the assets from their estate.

Additionally, because Ken and Lisa will be responsible for the income tax on the trust itself, they are eroding the assets of the trust less, which allows them to give more to their children in the long run while also removing additional assets from the estate (by using liquid assets that would otherwise be included in their estate to pay the tax liability).

KYLIE AND MAURICIO: HIGH NET-WORTH ENTREPRENEURS

Kylie and Mauricio are both in their 50s. They have been saving diligently for their retirement and other goals since they were quite young and have amassed a net worth of $15mm. They are both very philanthropic, giving annually to a donor-advised fund and taking an active role in their community.

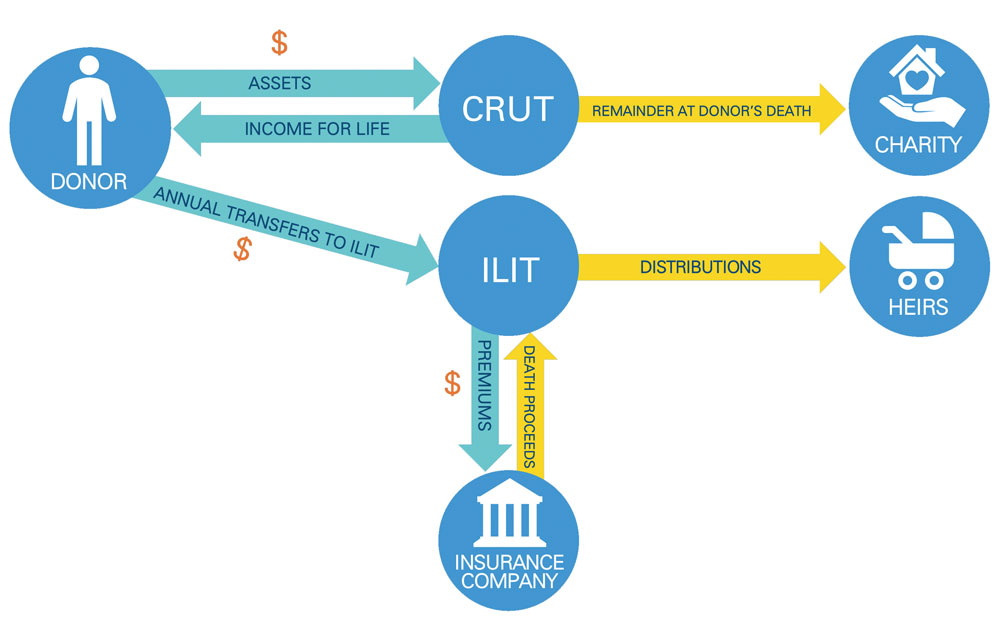

Kylie and Mauricio started an innovative tech business in Silicon Valley called EquineTech and are considering a potential sale of their business. Together, they want to minimize the tax impact on the sale and ensure that it does not hurt their retirement income needs (horses are an expensive hobby!).

Their planning solution, outlined in Diagram 3, involves donating shares of their business to a FLIP CRUT that begins as a Net Income Charitable Remainder Unitrust (“NICRUT”) that “flips” to a standard CRUT when Mauricio turns 62 (see “CRT” above for a refresher). When that happens, it pays 5% of the trust value to Kylie and Mauricio for their joint lifetimes, and the remainder goes into their donor advised fund that is run by their children. By contributing the shares of the business to the CRT, they will not be avoiding capital gains tax altogether, but will likely spread that tax out over several years, which, in most cases, results in a lower overall effective rate. This satisfies philanthropy and income in retirement.

When contributing a specialty asset, such as closely held business interests, it is vital that the donor has not made “substantial steps towards the completion of the sale.” If the IRS determines that substantial steps have been taken, they will force a realization of the capital gains.

Incorporating the next generation into the family’s planning via philanthropic giving is a great way to foster family unity, bequeath core familial values onto the next generation, and teach financial literacy. Forming a family board can be an effective way to define roles and develop a family heritage statement.

THE BIG PICTURE

If your tax burden is a pain point in your estate—particularly if you will be impacted by the current administration’s proposals and when the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act sunsets—and you have charitable intent, using your appreciated assets for philanthropic giving is worthy of consideration.

While the detailed nuances of satisfying purpose-driven philanthropy can get rather technical, the tax alleviation, fulfillment and familial unity that can result make the aforementioned strategies ideal for many estates in the equestrian community. If you would like additional information, have questions, or need an introduction to a tax advisor with expertise in this area, please contact me directly at (844) PLAN-YDF.

This article was originally published in National Horseman.

This educational article is for informational purposes only. Mr. Barse is not a CPA and does not offer tax advice. D. Vance Barse (CA Insurance #0L70885) is an investment adviser representative with and offers advisory services through Commonwealth Financial Network®, a Registered Investment Adviser.